On July 22, 1933, a statue of Harvey Scott was unveiled at the summit of Mount Tabor in Southeast Portland. Scott, a longtime editor of the Oregonian who opposed public schools and women’s suffrage, had died twenty-three years earlier. Scott’s family paid for the statue, and the sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, chose the site. Scott was depicted glowering and pointing toward the west. The eleven-foot statue was imposing, but puny compared to Borglum’s better-known works at Stone Mountain and Mount Rushmore.

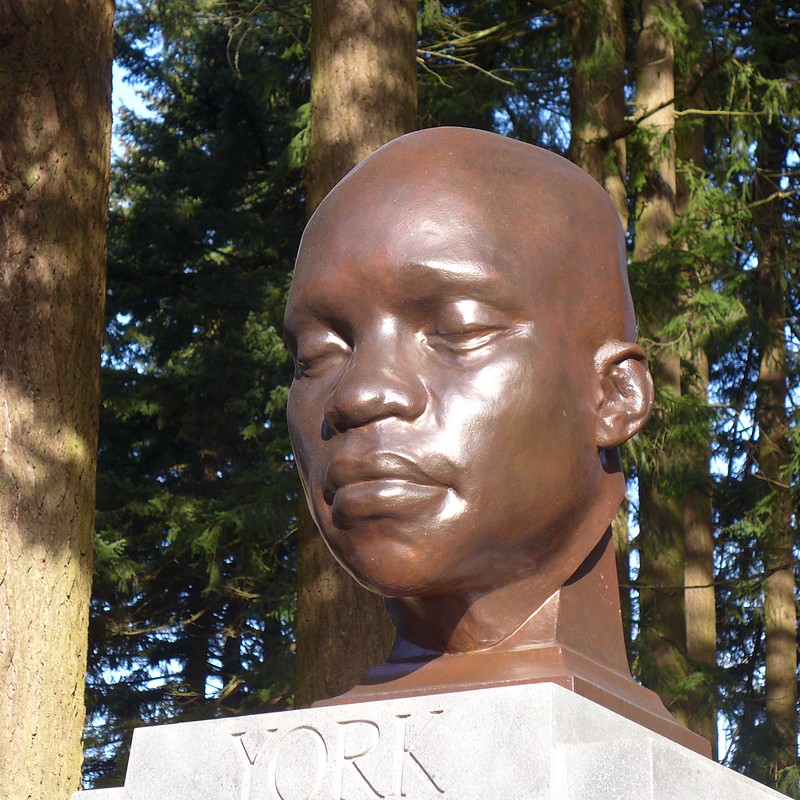

In October 2020, someone pulled the statue down. Its pedestal remained empty for four months. Then, in February 2021, an anonymous sculptor replaced it with a bust of York, a Black man who was enslaved by William Clark. York accompanied Clark and Meriwether Lewis on their expedition to the Pacific Northwest, and Clark refused to grant York his freedom for this service.

On July 28, 2021, someone smashed the bust. Today, the pedestal is empty.

No one alive today remembers Scott or York as people. Their statues represent ideas as much as they do individual human beings. The people who created, observed, and destroyed these symbols probably had very different notions of what they stood for.

In this issue, we explore how we remember and forget, as individuals and communities. Who and what do we remember? How are memories made and lost? And what, if anything, do they mean?

Ernst Borglum's statue of Harvey W. Scott. Photo by brx0, distributed under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 license.

The toppled statue. Photo by Ted Timmons, distributed under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Closeup of the bust of York. Photo by thekirbster, distributed under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

The empty pedestal in August 2021. Photo by Another Believer, distributed under a CC-BY-SA 4.0 license

Comments

No comments yet.