As a teenager, I worked a few nights a week at fast-food restaurants, from after school until late evening. At seventeen, I felt invincible walking down Powell Boulevard toward Burgerville. The street was—and still is—a very busy thoroughfare filled with a variety of businesses. To me, a fast-food joint was just another place to earn some extra cash.

At the time, I lived in a small duplex off 82nd Avenue, down the street from McDaniel High School (formerly Madison High School), where I attended. To get home, I’d take the nine bus line towards 82nd Avenue and then hop on number seventy-two. The entire trip normally took forty-five minutes.

By the time I arrived home, it would be close to midnight. Every time I opened my front door, there he was—my father, sitting in the living room waiting for me, sometimes with a cigarette in his hand. I’d stumble in quietly, exhausted and covered in grease, unable to decide whether I should take a shower or go to sleep.

“How was work?” he’d ask me.

“It was fine,” I’d reply unenthusiastically.

He usually grunted or nodded in response. Sometimes he said a few more words, but most of the time, he didn’t. After a long day, neither of us had much to say, so we formed a silent agreement—I’d go off to bed, and he would do the same.

I never thought about this particular exchange, about what it meant to me, until I got older. Sure, my dad could’ve gone to bed, but he didn’t. He waited to make sure I got home, and only when I did could he actually go to bed. I can imagine that as a parent, one of the worst fears you can have is to wake up and discover that your child has gone missing, that she never came home. My father never said this to me directly, but his actions speak more than words ever could.

To tell his story is to tell my mother’s story as well. I recently asked my mom about my father’s youth. After our conversation ended, I was filled with emotion. Their stories are so intertwined, one simply cannot exist without the other.

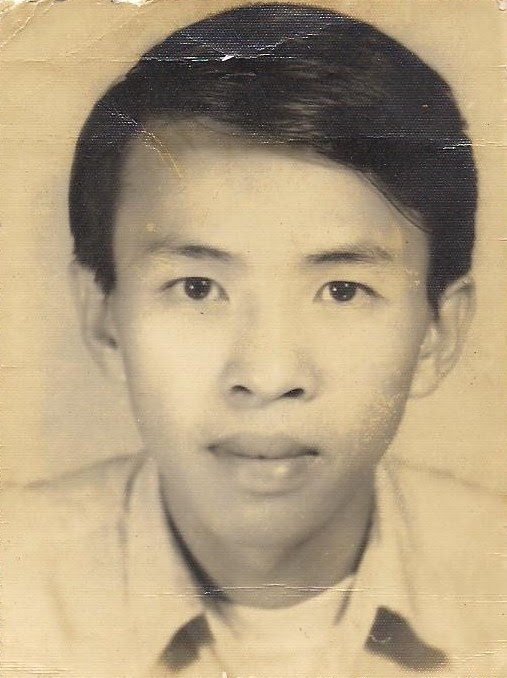

The author's parents, Le and Ly, photographed in the mid 1960s.

My dad, Le, was born in 1941 and my mom, Ly, in 1947. They lived in the same village in southern Vietnam, a place called Tra Co, where several generations of their families resided. Both of my parents were devout Catholics, and my father taught Sunday school for several years. They got married in 1964, an arranged marriage between the two families, when my dad was twenty-three and my mom was seventeen. They settled down to start a family while the Vietnam War raged on around them.

After they married, my dad joined the police force in southern Vietnam, presumably to help the South Vietnamese army as a plainclothes officer. He did this for two or three years until he was involved in an altercation that ultimately upended his (and my mother’s) life. There was an assassination attempt in which shots were fired and a higher-ranking officer died. My mom was not there, but she firmly believed my dad was innocent. Regardless of what happened, the men in his group were rounded up and taken to jail, including my dad.

Unfortunately, this occurred a month after my eldest brother, Long, was born in 1968. Tensions were growing steadily surrounding the war, both in the country and overseas. As a twenty-one-year old, my mom was suddenly thrust into single motherhood. So she lived with her in-laws (my father’s parents) and, with little choice in sight, she left Long in the care of his grandparents and went to work.

The whole time that my dad was in jail, from 1968 to 1974, my mother worked outside the home, mainly for the US military, doing cleaning and upkeep. During this time, she said, she saw a lot of Vietnamese and American romances occur around her, resulting in many mixed children. She admitted that she was tempted to get pregnant by an American so that she could claim citizenship for her child and go to America. But in the end, her piety and religious beliefs won over, and she didn’t do it. Mainly, she didn’t want to explain to her in-laws that she had a baby out of wedlock, and besides, she already had a child to worry about.

It was during this moment in our conversation that my mother’s voice rose fervently in octave. I sensed that she was reliving a past that she wanted to put behind her. Through her work, my mom found a way to make extra money by collaborating with the Americans. She said she convinced them to give her household items like soap, shampoo, and cleaners and then took those items and sold them outside for a profit. She did this for a while and was able to earn extra money for her ultimate goal—when her husband came home, they would have a house of their own. She never lost hope that this would happen.

Most of the money she made went to her in-laws, but she did save a little bit on the side. By the time my father got out of jail six years later, she had accumulated enough money (around 500,000 Vietnamese dong) to build a house. And that’s exactly what they did.

The author's parents in Vietnam shortly after the fall of Saigon.

After my father came home, she became pregnant again, and my brother Tony was born shortly after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Neither her family nor my father’s family were able to help with the building of their house, financially or with sweat labor. But now the war was over, and they could start fresh. Unfortunately, several months before Tony was born, another raid occurred, and bullets came through their village, destroying many homes, including theirs. Luckily, the foundation of my parents’ house was sturdy enough and it held up. To shoulder the blow, they evacuated to a nearby village and hid at a relative’s house until the fighting subsided.

However, it was not the first time that my mom had to go into hiding. In February 1969, when Long was just several months old, there was a surprise attack in the south, where she lived in the province of Dong Nai, in a city called Bien Hoa. She told me that because Long was born premature, he didn’t have the lungs to cry as loudly as a normal baby would, and because of that, they survived.

After the attack in 1975, my parents returned to their village with their sons and rebuilt their house, which became the home that I grew up in. During this time, my parents were dealt another blow. Like my parents, Vietnam was also trying to rebuild itself after the war, but it was a challenge. A series of unfavorable government decisions resulted in a major food shortage that would last for two years.

According to my mom, it was the hardest time of her life, not only because of the shortage, which forced her to dilute food with water and eat only what grew in their yard (including a lot of guava, bananas, and yams). She also had health problems and was diagnosed with endometriosis, a condition that can lead to infertility and causes extreme pelvic pain, which landed her in the hospital for several months.

Back then, doctors believed that the most effective way to treat the problem was to remove both fallopian tubes. My mother flatly refused, telling them that she wanted to have more children. They compromised, and the doctors ended up removing one of her tubes. She was told that she would most likely never have children again. Still, she continued to pray, she said.

About six years after her surgery, my mother realized that she was not feeling well and had not had her period for two months. She told my dad about her symptoms, the possibility of her being pregnant, but he scoffed. Like her, he had grown accustomed to the idea that their chances of conceiving another child were unlikely. It came as a surprise when I arrived in early 1985, stubborn and pink, with a full set of lungs to match.

Slowly, things got better. My parents began growing things in their yard for sustenance. We had a guava tree that produced an overabundance of fruit—I remember this tree fondly. But my dad chopped it down while drunk one day, angry because Tony kept climbing it.

By the early 90s, my mom was working outside of the home. Every morning, she rose early, before the light of dawn, and made a variety of snacks to sell at markets as a roving food vendor. She did this out of necessity because my father did not make any money. He was good with words, she said, but he couldn’t figure out a way to get people to pay him for it.

The author at age seven in the church where her father worked.

After the war ended, my father did some unpaid labor for the South Vietnamese government. Later, he volunteered at our church. It was to this church, the only one in our village, that he devoted the later years of his life, helping out with whatever was needed (unpaid, of course) including reciting prayers at church services, coordinating groups, planning events, and generally being a social butterfly. That was the father that I knew growing up. He earned the respect of many people who adored him and thought of him as a friend and mentor. He often appeared in photos with the priests by his side. There’s even one of me, wearing a yellow ao dai with the traditional hat, looking like a very awkward seven-year-old.

Still, the respect he received didn’t pay the bills. So my mom continued to work, even after we came to America in 1995, when we were sponsored by my uncle’s family. When my father died in 2003, hundreds of people attended his funeral. Whatever bad choices he made in his youth gave way to a more refined version of him. The father I knew was well-liked and respected, and he loved being around people. He was a good father to me, so much so that my first memory involves him.

At the time, I was four years old. For reasons unknown, I became sick for several weeks and had not gotten any better. When my parents took me to a local clinic, they were told that my condition was critical, and if they didn’t take me to the hospital right away I would die. So, my parents rushed me to the hospital. Every day for almost two weeks, while my mom was out working, my dad visited me. The memory of that experience still haunts me, because even after I’d seen a little boy lying very still on the bed next to mine (I later found out that he was already dead), I could still feel my father’s powerful love beside me. Whenever he visited me, he brought toys, trinkets, books, and soup—anything to make me feel better. Indeed, I got better.

This is how I will always remember him, and why I think highly of him still, even with all of his flaws. I know he wasn’t perfect, but by the time I came along, he had lived a life full of upheaval and tragedy, so I can imagine that he didn’t want to make any more mistakes.

Despite their precarious and unstable relationship, my parents were unyielding in their commitment to each other. During my teenage years, I witnessed them settling into their life together in America. I saw my dad hug my mom and my mom accept the touch. She was angry at him for many years, but in the end, when he passed, she was completely heartbroken. To this day, whenever the anniversary of his death comes around, April 28, her face becomes somber, and she laments the fact that he is no longer around for them to enjoy their retirement together, the unfairness of it all.

Both of my parents—my father especially—taught me that caring for someone means staying committed to them, being there by their side whenever they need you, never wavering. It is only when you’ve gone through all the ups and downs together, like my parents did, that you begin to appreciate all that there is—the simple joy of being together, of knowing there is someone out there caring for you.

Comments

2 comments have been posted.

Dry revealing and heartfelt. Thank you for sharing your the stories of your parents.

Justin | May 2022 | Eugene

This was a wonderful article. Keep up the great work!!

Dameion | May 2022 | Portland